Indus Valley Civilisation

The Indus or Harappan culture arose in the North-Western part of the Indian subcontinent.

It is called the ‘Harappan Civilisation’ because this was discovered first in 1921 at the modern site of Harappa, situated in the province of west Punjab in Pakistan.

It is also called as the ‘Indus Civilisation’ because it refers to precisely the same cultural, chronological and geographic entity confined to the geographic bounds of the Indus valley.

The civilisation belongs to the Chalcolithic or Bronze Age since the objects of copper and stone were found at the various sites of this civilisation.

Nearly, 1,400 Harappan sites are known so far in the sub-continent. They belong to the early, mature and late phases of the Harappan culture. But the number of sites belonging to the mature phase is limited, and of them only half a dozen can be regarded as cities.

Origin and Evolution

The discovery of India’s first and earliest civilisation posed a historical puzzle, as it seemed to have suddenly appeared on the stage of history, full grown and fully equipped.

The Harappan civilisation had shown no definite signs of birth and growth.

The puzzle could largely be solved after extensive excavation work was carried out, at Mehrgarh near the Bolan Pass between 1973 and 1980 by two French archaeologists, Richard H. Meadow and Jean Francoise Jarrige.

Mehrgarh gives us an archaeological record with a sequence of occupations. Archaeological research over the past decades has established a continuous sequence of strata, showing the gradual development to the high standard of the full-fledged Indus civilisation. These strata have been named pre-Harappan, early Harappan, mature Harappan and late Harappan phases or stages. By reviewing the main elements of the rural cultures of the Indian sub-continent the origin of the Indus civilisation can be traced. Any Pre-Harappan culture claiming ancestry to the Indus civilisation must satisfy two conditions.

The first condition is that it must not only precede but also overlap the Indus culture. The second is that the essential elements of the Indus culture must have been anticipated by the Proto-Harappan (Indus) culture in its material aspects, viz, the rudiments of town planning, provision of minimum sanitary facilities, knowledge of pictographic writing, the introduction of trade mechanisms, the knowledge of metallurgy and the prevalence of ceramic traditions.

The different stages of the indigenous evolution of the Indus can be documented by an analysis of the four sites, which reflect the sequence of the four important stages or phases in the pre-history and proto-history of the Indus valley region.

The sequence begins with the transition of nomadic herdsmen to settled agricultural communities as per the evidence found at the first site i.e. Mehrgarh near the Bolan Pass.

It continues with the growth of large villages and the rise of towns in the second stage exemplified at Amri. The Amri people did not possess any knowledge of town-planning or of writing.

The third stage in the sequence leads to the emergence of the great cities as in Kalibangan and finally ends with their decline, which is the fourth stage and exemplified by Lothal. Amri, Kot-Dijian and Kalibangan cultures are stratigraphically found to be pre-Harappan.

The four Baluchi cultures, viz, Zhob, Quetta, Nal and Kulli, undoubtedly pre-Harappan, also have some minor common features with the Indus civilisation, and cannot be considered as full-fledged proto-Harappan cultures.

The culture of Northern Baluchistan is termed as the ‘Zhob’ culture after the sites in the Zhob valley, the chief among them being Rana Ghundai. This culture is characterised by black and red ware and terracotta female figurines. Nal culture is characterised by the use of white-clipped ware with attractive polychrome paintings and the observance of fractional burial.

In the ‘early Indus period’, the use of similar kinds of pottery, terracotta Mother Goddess, representation of the horned deity in many sites show the way to the emergence of a homogenous tradition in the entire area.

The available evidence suggests that the Harappan culture had its origin in the Indus valley. And even within the Indus valley, several cultures seem to have contributed to evolve the urban civilisation. There is no evidence to suggest that the Indus people borrowed anything substantial from the Sumerians. It is thus difficult to accept Sir Mortimer Wheeler’s assumption that “the idea of civilization came to the Indus valley from Mesopotamia”.

Indus Valley Civilisation – Date and Extent- Town Planning

Date and Extent

The Harappan culture existed between 2500 BC and 1800 BC. Its mature phase lay between 2200 BC and 2000 BC. The advent of radiocarbon dating has provided a new sources of information in fixing the Harappan chronology.

The Indus civilization was the largest cultural zone of the period – the area covered by it (about 1.3 million sq.km.) being much greater than that of other contemporary civilisation. Over 1000 sites have discovered so far.

The discovery of new sites of this civilization has superseded the older theory. The relevant excavations have proved that the extent of the Harappan civilization covered an area of 1550 kilometers from north to south and about 1100 K. M. from west to east. It spread from Sut Kanjo Daro in Baluchistan in the west to Alarngirpore in Mirat district in U. P. and from Rupar in Hariyana to the Gulf of Cambay and the Bhagabar Valley in Gujarat.

The traces of the Harappan civilization have been found also in the Narmada Valley in Deccan. It is expected that further excavations will increase the extent of the Harappan civilization. There are reasons to believe that the Harappans spread their civilizations eastward. The older view that the Harappan culture was exotic and had no capacity to expand within the Indian sub-continent has lost its force due to the discovery of Harappan relics in wide areas of India.

The main centers of the Harappan civilization as revealed by the recent excavations are:

- Mohenjo-Daro in Sind. The town was situated on the bank of the Indus.

- Harappa in Punjab and the town was situated on the bank of the Ravi.

- Kalibangan in Rajasthan situated on the bank of the Gharghara.

- Rupar in Hariyana situated on the bank of the Sutlej.

- Lothal in Gujrat situated on the bank of the Bhagawar River.

- Rangpore in Gujrat.

- The Narmada and the Tapti belt.

Town Planning

Urban-Town Planning

The excavation undertaken in various places gives clear indication that the people of the Indus Valley were primarily urban people. The Indus cities, whether Harappa or Mahenjo-daro in Pakistan or Kalibangan, Lothal or Sarkotada in India; shows town planning of a truly amazing nature. In both the places the cities were built on a uniform plan.

To the west of each town was a ‘citadel’ mound built on a high podium of mud-brick and to the east was the town proper the main hub of the residential area. The citadel and the town were further surrounded by a massive brick wall. In fact careful planning of the town, fine drainage system, well arranged water supply system prove that all possible steps were carefully adopted to make the town ideal and comfortable for the citizenry.

The street lights system, watch and ward arrangement at night to outwit the law breakers, specific places to throw rubbish and waste materials, public wells in every street, well in every house etc. revealed the high sense of engineering and town planning of the people. The main streets, some as wide as 30 to 34 feet were laid out with great skill dividing the cities into blocks within which were networks of narrow lanes. The streets intersected in right angles and so arranged that the prevailing winds could work as a sort of suction pump and thereby clean the atmosphere automatically.

No building was allowed to be constructed arbitrarily and encroaching upon a public highway. The owners of the pottery kilns were not allowed to build the furnaces within the town, obviously to save the town from air pollution.

The drainage system managed by the Indus Valley civilization is indeed unique. The idea and the system were highly scientific and by all means best of the time. The drainage system of Mahenjo-daro is so elaborate and scientific that a similar advanced system has not been found in any town of the same antiquity.

House drains connected in the main drains running under the main streets and below many lanes. Drains were made of gypsum, lime and cement, covered with portable stabs. In regular intervals, there were inspection traps and main-holes for inspection. Main drains were feet 2½ to 5 ft. broad. The small drains were connected with main drains which helped to pull water speedily out of the town. Every house had an independent soak- pit which collected all sediments and allowed water to flow to the main drains passing underneath the main streets of the town.

Proper care was taken to ensure that the house-wives did not throw refuse and dirt in the drains. The extensive drainage system adopted by the people of the Indus Valley unhesitatingly proves that the people of the time had developed a high sense of health and sanitation. The people of Indus Valley had generally constructed three types of buildings, such as dwelling houses, public halls and public baths. Burnt bricks were used and fixed skillfully with the help of mud and mortar for the construction of houses and other different structures of the towns. Buildings were of different sizes but generally were single or double storied.

From the existence of a staircase, it is evident that double storied dwelling houses were widely prevalent. The houses were furnished with paved floors and were provided with doors and windows. The roofs were made of mud, reed and wood. Every house possessed a well both room courtyard kitchen and first class drainage network.

The houses were more or less typified the same plan, a square courtyard round of which a number of rooms. Almost every house had a bathroom at the ground floor and some even on the first floor. The bathrooms were connected by a drainage channel to sewers in the main streets leading to soak-pits. The domestic drainage system and the bathing structures and the outlets are found to be very remarkable.

The average size of the ground floor of a house was about 11 square metres but there existed many bigger houses. Some barrack-like groups of single roomed tenements have been discovered at Mahenjo-daro and Harappa, similar to the coolie lines of Indian tea and other estates. Many public buildings have come to notice during excavation; for example, a high pillared hall having an area of 80 sq. feet came to light, which is accepted to have been used as an assembly hall for transacting matters of common interest.

The great public bath excavated in Mahenjo-daro is really significant. It was thought provoking how a massive bath could be constructed 5000 years ago. It is 180 feet by 180 feet square. The bricks used were of different sizes. Some were 20 inches by 8 inches and the smaller were 9 inches by 4 inches. The great bath is surrounded by a large number of rooms. It has a flight of steps at either end and is fed by a well situated adjoining room. There were separate drainage systems to flush out waste and dirty water. The actual bathing pool is about 139 feet in length and 23 feet in breadth and the depth is 8 feet. It is presumed that this great bath was used by the members of the public on auspicious festive days. The strength and the durability of the structure prove amply that it could last 5000 years with standing all kinds of ravages of nature.

To the west of the Great Bath existed a remarkable group of 27 blocks of brick-work crisscrossed by narrow ventilation channels. This structure is the podium of the great granary. It is 200 feet long and 150 feet wide and further sub-divided into smaller storage blocks for storing different types of grains generally used during the period of food crisis.

Indus Valley Civilisation – Economic Life – Trade and Commerce

Political Organisations/Municipalities

Despite a growing body of archaeological evidence, the social and political structures of the Indus culture remain objects of conjecture. The apparent craft specialisation, along with the great divergence in house types and size, points to some degree of social stratification. Trade was extensive and apparently well-regulated.

The remarkable uniformity of weights and measures and development of many civil works such as construction of great granaries, imply a strong degree of political and administrative control over a wide area.

Further, the widespread occurrence of inscriptions in the Harappan script almost certainly indicates the use of a single lingua franca, a sign of social coherence.

Economic Life

The nature of the Indus civilization’s agricultural system is still largely a matter of conjecture due to the paucity of information surviving through the ages. Some speculation is possible, however.

The Indus civilization agriculture must have been highly productive; after all, it was capable of generating surpluses sufficient to support tens of thousands of urban residents who were not primarily engaged in agriculture.

It relied on the considerable technological achievements of the pre-Harappan culture, including the plough. Very little is known about the farmers who supported the cities or their agricultural methods. Some of them undoubtedly made use of the fertile alluvial soil left by rivers after the flood season, but this simple method of agriculture is not thought to be productive enough to support cities. There is no evidence of irrigation, any such evidence could have been obliterated by repeated, catastrophic floods.

The Indus civilization appears to contradict the hypothesis of the origin of urban civilization and the state. According to this hypothesis, cities could not have arisen without irrigation systems capable of generating massive agricultural surpluses. To build these systems, a despotic, centralized state emerged that was capable of suppressing the social status of thousands of people and harnessing their labor as slaves. It is very difficult to square this hypothesis with what is known about the Indus civilization, as there is no evidence of kings, slaves, or forced mobilization of labor.

It is often assumed that intensive agricultural production requires dams and canals. This assumption is easily refuted. Instead of building canals, the Indus civilization people may have built water diversion schemes, which, like terrace agriculture, can be elaborated by generations of small-scale labor investments.

In addition, it is known that the Indus civilization people practiced rainfall harvesting, a powerful technology that was brought to fruition by classical Indian civilization but nearly forgotten in the twentieth century. It should be remembered that Indus civilization people, like all peoples in South Asia, built their lives around the monsoon, a weather pattern in which the bulk of a year’s rainfall occurs in a four-month period. At a recently discovered Indus civilization city in western India, archaeologists discovered a series of massive reservoirs, hewn from solid rock and designed to collect rainfall, that would have been capable of meeting the city’s needs during the dry season.

Trade and Commerce

The Harappan cities were bustling centers of industry, trade and commerce. Carpenters, metal-smiths, weavers, gold-smiths and jewellers produced goods of high quality which were in demand within as well as outside the Harappan territory.

Government and municipal servants regulated and maintained municipal services, weight and measures and trade routes.

Merchants carried on trade in cotton as well as finished goods within and outside the country. Bullock carts, pack animals, boats and sea – going ships were used to transport goods. Objects like pottery, stone beads and metal – ware originating in one region but found in other cities are evidence of extensive trade. Harappan type seals found at Bahrain and in Mesopotamian cities provide evidence of extensive overseas trade.

Cotton was the most important item of export. Lapis lazuli was imported from Central Asia, gold from Karnataka and copper and possibly, also tin, from Mesopotamian.

Seals were affixed by merchants to bales or parcels of their goods as trademarks or proofs of ownership.

Indus Valley Civilisation – Art and Craft – Harrapan Seals – Important Seals

Art and Craft

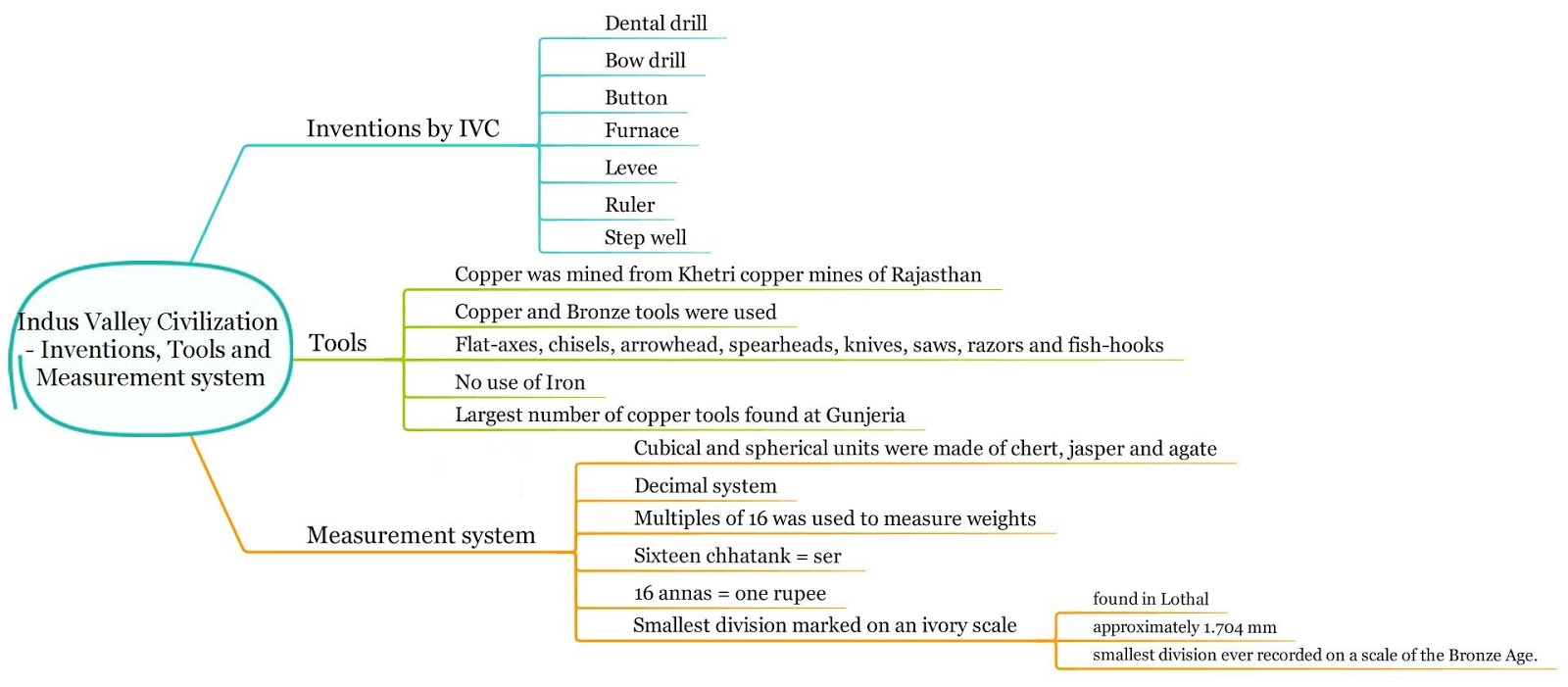

The Harappan culture belongs to the Bronze Age. The people of Harappa used many tools and implements of stone, but they were well-acquainted with the manufacture and use of bronze. However, bronze tools are not prolific in Harappa.

For making bronze, copper was obtained from the Khetri copper mines at Rajasthan and from Baluchistan, and tin from Afghanistan. The bronze-smiths produced not only images and utensils but also various tools and weapons such as axes, saws, knives and spears.

A piece of woven cotton has been recovered from Mohenjo-daro, and textile impressions have been found on several objects. Spindle whorls and needles have also been discovered. Weavers wove cloth of wool and cotton. Boat making was practised.

Seal-making and terracotta manufacture were also important crafts. The goldsmiths made jewellery of silver, gold, copper, bronze and precious stones. Silver and gold may have been obtained from Afghanistan and precious stones from South India.

The Harappans were expert bead-makers. Also, the potter’s wheel was in full use.

The Harappans were not on the whole extravagant in their art. The inner walls of their houses were coated with mud plaster without paintings. The outer walls facing the streets were apparently of plain brick. Architecture was austerely utilitarian. Their most notable artistic achievement was perhaps in their seal engravings, especially those of animals, e.g., the great urns bull with its many dewlaps, the rhinoceros with knobbly armoured hide, the tiger roaring fiercely, etc.

The red sandstone torso of a man is particularly impressive for its realism. The bust of another male figure, in steatite, seems to show an attempt at portraiture.

However, the most striking of the figurines is perhaps the bronze ‘dancing girl, found in Mohenjo-daro. Naked but for a necklace and a series of bangles almost covering one arm, her hair dressed in a complicated coiffure, she stands in a provocative posture, with one arm on her hip and one lanky leg half-bent.

The Harappans made brilliantly naturalistic models of animals, specially charming being the tiny monkeys and squirrels used as pinheads and beads. For their children, they made cattle-toys with movable heads, model monkeys which would slide down a string, little toy-carts, and whistles shaped like birds, all of terracotta. They also made rough terra cotta statuettes of women, usually naked or nearly naked, but with elaborate headdresses; these are probably icons of the Mother Goddess.

Harrapan Seals

The most interesting part of the discovery of the Harrapan Civilisation relates to the seals. More than 2000 in number, these were made of soapstone, terracotta and copper.

The seals give us useful information about the civilization of Indus valley. Some seals have human or animal figures on them. Most of the seals have a knob at the back through which runs a hole. They also have the figures of real animals while a few bear the figure of mythical animals. The seals are rectangular, circular or even cylindrical in shape.

The seals even have an inscription of a sort of pictorial writing. It is said that these seals were used by different associations or merchants for stamping purposes. They were also worn round the neck or the arm.

The seals show the culture and civilization of the Indus Valley people. In particular, they indicate:

- Dresses, ornaments, hair-styles of people.

- Skill of artists and sculptors.

- Trade contacts and commercial relations.

- Religious beliefs.

Important Seals

- The Pashupati Seal

This seal depicts a yogi, probably Lord Shiva. A pair of horns crown his head. He is surrounded by a rhino, a buffalo, an elephant and a tiger. Under his throne are two deer.

The seal shows that Shiva was worshipped and he was considered as the Lord of animals (Pashupati).

- The Unicorn Seal

The unicorn is a mythological animal. This seal shows that at a very early stage of civilization, humans had produced many creations of imagination in the shape of bird and animal motifs that survived in later art.

- The Bull Seal

This seal depicts a humped bull of great vigour. The figure shows the artistic skill and a good knowledge of animal anatomy.

Indus Valley Civilisation – Religion – Script – Decay and End

Religion

It is widely suggested that the Harappan people worshipped a Mother Goddess symbolizing fertility.

A few Indus valley seals display the swastika sign, which were there in many religions, especially in the Indian religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism.

The earliest evidence for elements of Hinduism is before and during the early Harappan period. Symbols close to the Shiva lingam have been located in the Harappan ruins.

One famous seal displayed a figure seated in a posture reminiscent of the lotus position, surrounded by animals. It came to be labelled after Pashupati (lord of beasts), an epithet of Shiva.

The discoverer of the Shiva seal (M420), Sir John Marshall and others have claimed that this figure is a prototype of Shiva, and have described it as having three faces, seated on a throne in a version of the cross-legged lotus posture of Hatha Yoga. A large tiger rears upwards by the yogi’s right side, facing him. This is the largest animal on the seal, shown as if warmly connected to the yogi; the stripes on the tiger’s body, also in groups of five, highlight the connection. Three other smaller animals are depicted on the Shiva seal. It is most likely that all the animals on this seal are totemic or heraldic symbols, indicating tribes, people or geographic areas. On the Shiva seal, the tiger, being the largest, represents the yogi’s people, and most likely symbolizes the Himalayan region. The elephant probably represents central and eastern India, the bull or buffalo south India and the rhinoceros in the regions west of the Indus River.

What are thought to be linga stones, have been dug up. Linga stones in modern Hinduism are used to represent the erect male phallus or the male reproductive power of the god Siva. But again, these stones could be something entirely different from objects of religious worship. The deity sitting in a yoga-like position suggests that yoga may have been a legacy of the very first great culture that occupied India.

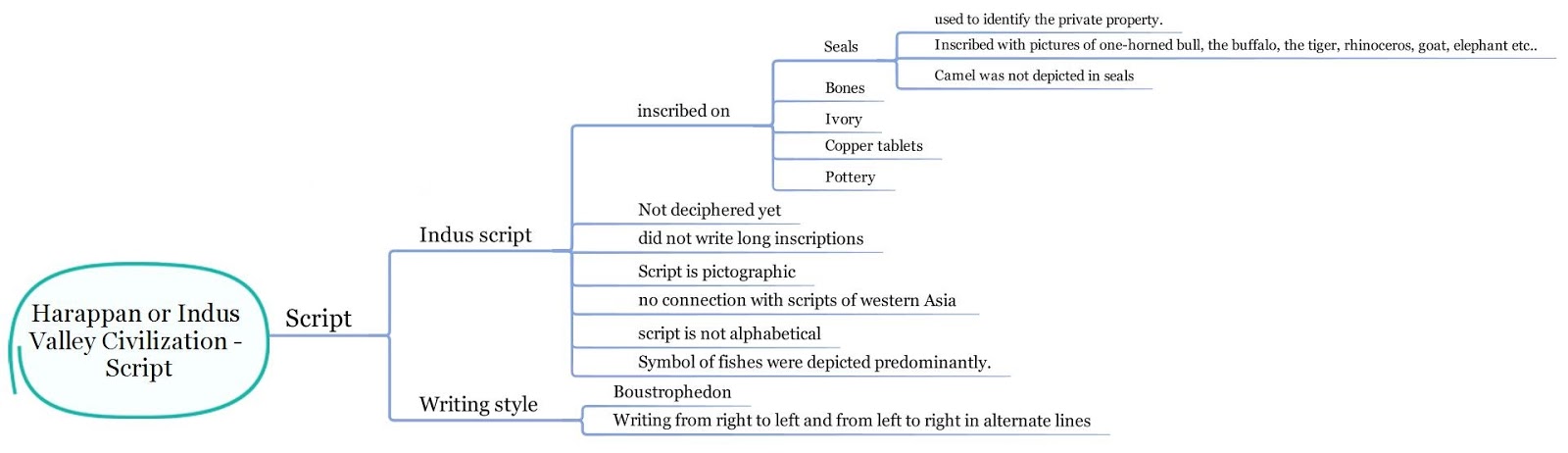

Script

The Indus script (also known as the Harappan script) is a corpus of symbols produced by the Indus Valley Civilization during the Kot Diji and Mature Harappan periods between 3500 and 1900 BCE.

Most inscriptions containing these symbols are extremely short, making it extremely difficult to judge whether or not these symbols constitute a script used to record a language, or even symbolise a writing system. In spite of many attempts, ‘the script’ has not yet been deciphered, but efforts are ongoing. There is no known bilingual inscription to help decipher the script, nor does the script show any significant changes over time. However, some of the syntax varies, depending upon the location.

The first publication of a seal with Harappan symbols dates to 1875, in a drawing by Alexander Cunningham. Since then, over 4,000 inscribed objects have been discovered, some as far afield as Mesopotamia.

In the early 1970s, Iravatham Mahadevan published a corpus and concordance of Indus inscriptions listing 3,700 seals and 417 distinct signs in specific patterns. He also found that the average inscription contained five symbols,

Decay and End

By 1900BC, many of the Indus Valley cities had been abandoned. Historians believe things started to fall apart around 1700BC. But how did this apparently peaceful, well-organised civilisation collapse in just 200 years?

Looking at the ruins we can see many changes. The cities became overcrowded, with houses built on top of houses. Important buildings like the Great Bath at Mohenjo-Daro were built over.

People stopped maintaining the drains and they became blocked. Some traders even hid their valuables under the floors of their homes. Trade was very important for the Indus civilisation. Their main trade partner was Mesopotamia, which was an advanced civilisation in the Middle East.

Around the time the Indus cities started to fail, Mesopotamia was going through huge political problems. Their trade networks collapsed and this would have had a big impact on the Indus cities. There would have been less work for traders and for manufacturers, who made the things which the traders sold abroad. Some historians think this is why the cities collapsed.

We know that only the cities fell into ruins. Farmers in the Indus Valley went on living in their villages and working on their farms, but the civilisation would never return to greatness again.

Some historians believed the Indus civilisation was destroyed in a large war. Hindu poems called the Rig Veda (from around 1500BC) describe northern invaders conquering the Indus Valley cities. In the 1940s, archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler discovered 39 human skeletons at Mohenjo-Daro. He believed that they were people killed by invaders. Archaeologists now think this is not true. There is no evidence of war or mass killings. Indus Valley people seem to have been peaceful. If they had an army, they have left few signs of weapons or battles.

It is more likely that the cities collapsed after natural disasters. Enemies might have moved in afterwards. Movements in the Earth’s crust (the outside layer) might have caused the Indus river to flood and change its direction. The main cities were closely linked to the river, so changes in the river flow would have had a terrible effect on them. Repeated flooding may have led to a build-up of salt in the soil, making it hard to grow crops.

It is believed that at the same time, the Ghagger Hakra River (an important river in the area) dried up. People were forced to abandon many of the cities located along its banks, such as Kalibangan and Banawali. People would have starved and diseases would have spread. Perhaps because of this chaos, the rulers lost control of their cities.

Important Sites of the Indus Valley Civilisation

Harrapa

Harappa is a large capital of the Indus Civilization, and one of the best-known sites in Pakistan, located on the bank of the Ravi River in central Punjab Province.

At the height of the Indus civilization, between 2600-1900 BC, Harappa was one of a handful of central places for thousands of cities and towns covering a million square kilometers (about 385,000 square miles) of territory in South Asia.

Harappa was occupied between about 3800 and 1500 BC: and, in fact, the modern city of Harappa is built atop some of its ruins. At its height, it covered an area of at least 100 ha (250 ac) and may have been about twice that, given that much of the site has been buried by the alluvial floods of the Ravi river.

Intact structural remains include those of a citadel, a massive monumental building once called the granary, and at least three cemeteries. Much of the adobe bricks of significant architectural remains were robbed in antiquity.

Mohenjo- Daro

Mohenjo-daro is widely recognized as one of the most important early cities of South Asia and the Indus.

Discovery and Major Excavations

Mohenjo-daro was discovered in 1922 by R. D. Banerji, an officer of the Archaeological Survey of India, two years after major excavations had begun at Harappa, some 590 km to the north. Large-scale excavations were carried out at the site under the direction of John Marshall, K. N. Dikshit, Ernest Mackay, and numerous other directors through the 1930s.

Although the earlier excavations were not conducted using stratigraphic approaches or with the types of recording techniques employed by modern archaeologists they did produce a remarkable amount of information that is still being studied by scholars today.

The historical city’s original name is not Mohenjo Daro. Nobody knows what the real name is, as the Harrappan scripture has still not been deciphered. The words ‘Mohenjo Daro’ literally translate to ‘the mound of the dead’. The city of Harappa and other important Indus Valley sites were found on a series of mounds over 250 acres of land, hence such a name

The urban planning and architecture have mesmerised thousands of architects and archaeologists. The 5,000-year-old city could host a population of 40,000. It had a meticulous road plan with rectilinear buildings, channeled sanitisation, a huge well that served as a public pool to bathe, a ‘Great Granary’, and many more amazing designs on buildings. It is also fascinating that multi-storeyed buildings were found at the site of Harappa and Mohenjo Daro

There are signs that prove that the Indus Valley Civilisation had no monarchy. It was probably governed by an elected committee.

The lifestyle and faith of the people of Harappa and Mohenjo Daro are still under doubt. Some artefacts, such as the Pashupati Seal, suggest that the people would worship an ‘animal deity’, who would protect them from wild beasts.

Alamgirpur

Located in the Meerut district of Uttar Pradesh, Alamgirpur is the eastern most site of the Indus Valley Civilization. This site is located very near to the Hindon river.

Alamgirpur respectively belonged to (I) Harappan, (II) Painted Grey Ware (III) Early historical and (IV) Late Medieval Period.

The site was partially excavated in 1958 and 1959 by Archaeological Survey of India. On excavation, the site showed four cultural periods with intervening breaks; the earliest of them represented by a thickness of 6 feet, belonged to the Harappan Culture.

The site was partially excavated in 1958 and 1959 by Archaeological Survey of India. On excavation, the site showed four cultural periods with intervening breaks; the earliest of them represented by a thickness of 6 feet, belonged to the Harappan Culture.

Although kiln burnt bricks were in evidence, no structure of this period was found, probably due to the limited nature of the excavations. Brick sizes were, 11.25 to 11.75 in. in length,5.25 to 6.25 in. in breadth and 2.5 to 2.75 in.in thickness; larger bricks averaged 14 in. x 8 in.x 4 in. which were used in furnace only.

Typical Harappan pottery was found and the complex itself appeared to be a pottery workshop. Ceramic items found included roof tiles, dishes, cups, vases,cubicle dice, beads,terracotta cakes, carts and figurines of a humped bull and a snake.

There were also beads and possibly ear studs made of steatite paste, faience, glass, carnelian, quartz, agate and black jasper. Little metal was in evidence. However, a broken blade made of copper was found.

The head of a bear being a part of a vessel was discovered at Alamgirpur. A small terracotta bead-like structure was coated with gold. Evidence of cloth is found in way of impressions on a trough.

Kalibangan

The site Kalibangan – literally ‘black bangles’ – derives its name for the dense distribution of the fragments of black bangles which were found at the surface of its mounds.

Evidence of this period consists of a citadel area over the 1.6 metre-thick early Harappan deposit in Kalibangan-1 (the western mound of the site, a chessboard pattern ‘lower city’ in Kalibangan-2 (the lower and larger eastern mound), and a mound full of fire altars in a much smaller mound further east (Kalibangan-3).

The citadel complex of KLB-1 is roughly a parallelogram (240 by 120 metres) divided into two equal parts with a partition wall and surrounded by a rampart with bastions and salients. The basil width of the fortification wall is 3-7 metres. The wall is made of mud bricks in a ration of 4:2:1, with mud plaster on both the inner and outer faces. The southern half of the citadel had ceremonial platforms and fire altars. Fire altars were also built in residences where a room was apparently earmarked for them. The altars were renewed from time to time as the general level of the site became higher.

There were two entrances to the Kalibangan citadel complex, one to the north and the other to the south. The southern entrance has a brick structure about 2.6 metres wide with oblong salients on both sides of the step of the entrance. The northern structure has a mud brick staircase. The northern half of the citadel area complex had a street, and housed the elite. In the southern half fire altars were arranged in a row on top of platforms constructed for this purpose. Stairs provided access to the top, and the ground around the platforms was paved with bricks.

The lower city (KLB-2) was also fortified and laid out in a chessboard pattern, and built of mud bricks of the standard 4:2:1 proportion. The basis shape is that of a parallelogram measuring 235 x 360 metres. The basal width of the fortification wall is 3.5-9 metres. The streets run north – south and east -–west, dividing the area into blocks, and are connected to lanes. There were mud brick rectangular platforms by the side of the roads. Wooden fender posts were intended to ward off damage to street corners. House drains of mud brick and wood discharged into jars in the streets, above the ground. In some areas, the streets were paved with terracotta nodules.

The lower city had entrances on the northern and western sides. Each house consisted of six or seven rooms, with a courtyard or a corridor between the rooms. Some rooms were paved with tiles bearing designs.

KLB-3, the isolated easternmost mound, has brought to the surface a row of fire altars, and this find, along with the remains of fire altars in KLB-1 mentioned above is clear evidence that fire altars played a major role in the religious life of the people.

Interesting evidence regarding cooking practices is revealed by the presence of both underground and overground varieties of mud ovens inside the houses. These ovens closely resemble the present-day tandoors which are used in Rajasthan and Punjab. The underground variety was made with a slight overhang near the mouth, while the overground ovens were given a bridged side opening for feeding fuel and were plastered periodically. The ovens were perhaps used for baking bread, as the Kalibangan residents were mainly wheat eaters. The wheat grains were most likely stored in cylindrical pits lined with lime plaster, which have been discovered at the site.”

Kot Diji

Kot Diji is an archaeological site located near an ancient flood channel of the Indus River in Pakistan, 15 miles (25 km) south of the city of Khairpur in Sindh province.

The site, which is adjacent to the modern town of Kot Diji, consists of a stone rubble wall, dating to about 3000BC, that surrounds a citadel and numerous residences, all of which were first excavated in the 1950s.

The origins of Kot Diji are recognized as belonging to the early Harappan period, which dates to about 3500BC. Although Kot Diji lasted through the mature Harappan period (about 2600–1750BCE), a layer of burned debris separates structures of the early and the mature periods, which suggests that the settlement was at some point heavily damaged by fire. Artifacts, including pottery, that display a distinct Kot Dijian style have been excavated from Kot Diji and other archaeological sites in the region.

Kot Diji is located in the vicinity of several other important historic sites. It sits to the east of Mohenjo-daro, a group of mounds that contain the remains of what was once the largest city of the Indus civilization.

Lothal

Lothal, literally “Mound of the Dead”, is the most extensively excavated site of the Harappan culture in India, and therefore allows the most insight into the story of the Indus Valley Civilization, its exuberant flight, and its tragic decay.

Once a sleepy pottery village, Lothal rumbled awake to become a flourishing centre of trade and industry, famous for its expertly constructed system of underground sanitary drainage, and an astonishing precision of standarized weights and measures.

Unlike many other doorways into Harappan culture, Lothal passed through all the phases of the society, from earliest development to most mature. In the height of its prosperity, it not only survived but was strengthened by three floods, using the disaster as an opportunity to improve on the infrastructure. The fourth flood finally brought the settlement to the desperate and impoverished conditions that indicated the end of a powerful civilization.

Lothal holds the third largest collection of seals and sealings, engraved on steatite, with animal and human figurines and letters from Indus script, but these remain undeciphered, so they do not provide as much insight into the material culture as the other findings. They do however show aspects of the spiritual culture; there are signs of worship of fire, and of the sea goddess, but not of the mother goddess.

Lothal had a highly developed bead-making industry. It was famous for its micro-beads that were made by rolling ground steatite paste on string, baking it solid, and then cutting it with a tiny saw into the desired lengths. The expertise is evident in the micro-beads of gold under 0.25 mm in diameter which cannot be found anywhere else. The gold, like today, was most likely only for the upper classes, while the poorest citizens had to make do with shell and terracotta ornaments.

Lothal was believed to be Dravidian, but recent findings of association with Vedas and other Sanskrit scriptures lead some to believe this was the cradle of Aryan civilization in the sub-continent. There does seem to be enough evidence to suggest non-Aryan origin, and strong Aryan influence, as well as a meeting of the cultures, both violent and peaceful.

Amri

The archaeological importance of Amri was demonstrated in 1929 by the excavations of N.G.Majumdar, who discovered there, for the first time, a settlement of pre-Harappan date and culture that was underlying a Harappan one.

There are four successive periods of occupation. The first of these is the ‘Amrian’, which relates to other pre-Harappan sites in the region as well. Amri is the type-site of this early cultural assemblage. In this phase, houses were of mud-brick. Pottery, copper and bronze fragments were also recovered. Phase II shows an increasing component of Harappan materials alongside the Amrian. Period III belongs to the Harappan, giving evidence of early, transitional, and late sub-phases, into a final ‘Jhukar’ sub-phase. The final phase, Period IV, is not well represented, but it produced the coarse grey ware comparable to the sites of the ‘Jhangar’ complex.

The early occupation at Amri has been dated between 3600 and 3300 BC, and thus represents a slightly later phase than Balakot. Amri is located close to the west bank of the Indus River but also only some 10 kilometres from the easternmost extension of the Baluchistan uplands. It is in the Dadu district of Sindh, and lies to the south of Mohenjo Daro. The site comprises two main archaeological mounds, A in the east and B in the west.

Amri Phase pottery is a red-buff ware, mainly hand-made, and includes such vessel forms as angular-walled and hemispherical bowls, dish-on-stand (rare), and most commonly S-shaped jars. Black, brown and red paint were applied to the vessel’s surface or to a cream or buff slip or wash in monochrome or bichrome schemes. Decorative schemes emphasized geometric motifs in horizontal bands with frequent use of ‘checkerboard’ and ‘sigma’ motifs.

In the later Amri phase, motifs become more complicated and involve the use of intersecting circles, ‘fish-scale’ motifs, zoomorphic motifs and the rare use of red slip. Other terracotta objects include beads, bangles, humped cattle figurines, and circular, square and triangular cakes.

Stone tools are similar to other phases except that there was an emphasis on geometric microliths. Only the following additional type objects have been identified: carnelian beads (rare), shell bangles, bone points and bangles, a steatite rod and a copper blade. Certainly ceramic craft specialists were present, but it is difficult now to establish certainly other types of full- or part-time specialists.

Chanhudaro

Chanhudaro (also Chanhu Daro) is an archaeological site belonging to the post-urban Jhukar phase of Indus valley civilization. The site is located 130 kilometers south of Mohenjo-daro. The settlement was inhabited between 4000 and 1700 BCE, and is considered to have been a centre for manufacturing carnelian beads. This site is a group of three low mounds that excavations have shown were parts of a single settlement, approximately 5 hectares in size.

Rupar

Rupar is another Indus Valley site. At Rupar excavation, the lowest levels have yielded the Harappan traits in Period 1, which falls in the proto-historic period. A major find has been a steatite seal in the Indus script used for the authentication of trading goods, impression of seal on a terracotta lump of burnt clay, chert blades, copper implements, terracotta beads and bangles and typical standardized pottery of Indus Valley Civilization. They flourished in all the Harappan cities and townships.

The dead were buried with their head generally to the north and with funerary vessels. What led the Harappans to desert the site is not known.

Banawali

Banawali is an archaeological site belonging to the Indus Valley Civilization period. It is in the Fatehabad district of Haryana and is located about 120 km northeast of Kalibangan.

In comparison with Kalibangan, which was a town established in the lower middle valley of the dried up Sarasvathi River, Banawali was built over the upper middle valley of Sarasvathi River.

Well planned houses were constructed out of kiln burnt and moulded bricks. Pottery consisting of vases and jars, and is divided into two groups, based on general design. Pottery assemblage is very similar to those of Kalibangan I period.

The Archaeological Survey of India has done excavation in this place, and has revealed a well constructed fort town of the Harappan period, overlaying an extensive proto urban settlement of the pre- Harappan Period. A defence wall was also found with a height of 4.5 m and thickness of 6 m which was traced up to a distance of 105 m.

Houses, with rammed earthen floors, were well planned with rooms and toilets and houses were constructed on either sides of streets and lanes.

Near the south-eastern area of the fortification, a flight of steps has been found rising from the ‘Lower town’ to the Acropolis, and the ASI considers this as important formation. The staircase of the ‘lower town’ is near a bastion looking construction.

Surkotada

Surkotada is a small, 3.5 acre site northeast of Bhuj, in Gujarat. The mound has an average height of five-to-eight metres (east-to-west).

At the time of its discovery, the mound at Surkotada appeared to be a potential site with not only its available rubble fortifications exposed at places on the surface itself but also having an adjacent lower area yielding Harappan and other pottery and antiquities. The excavations at Surkotada have been significantly rewarding in unfolding a sequence of three cultural sub-periods well-within the span of Harappan chronology and this fact has been attested to by the C-14 dating, i.e. circa 2300 B.C. to 1700 B.C.

The Harappans had a fortified citadel and residential annexe in Period IA and the same pattern of settlement had been maintained through the successive sub-periods IB and IC.

Almost all the pottery shapes were in conformity with the material available at other Harappan sites.

At Surkotada, throughout, a compact citadel and residential annexe complex has been found, but no city complex has been unearthed.

Sutkagan Dor

Sutkagan Dor (or Sutkagen Dor) is the westernmost known archaeological site of the Indus Valley Civilization. It is located about 480 km west of Karachi on the Makran coast, near the Iranian border, in Pakistan’s Baluchistan Province. The site is near the western bank of the Dasht River and its confluence with a smaller stream, known as the Gajo Kaur. It was a smaller settlement with substantial stone walls and gateways.

Sutkagan Dor was discovered in 1875 by Major Edward Mockler, who conducted a small-scale excavation.

In October 1960, Sutkagan Dor was more extensively excavated by George F. Dales as a part of his Makran Survey, uncovering structures made from stone and mud bricks without straw.

Tools & Measurement System

Skills & Occupations

No comments